Learning to read your built environment – your city – helps you to form tangible connections to where you live. In turn, your sense of place and community increases. You feel ownership and responsibility for your town or city, which allows for better planning and smart development. The longer you live somewhere and study, the better you get to know a place; the more you love it.

But what happens you go someplace new? How do you read the built environment if you know nothing about its history? Good question. The best part of learning to read the layers of the built environment is that you can gain a sense of place and understanding without needing to know its cultural history. How do you do that? By observing and translating the elements of the built environment you see the development and changes.

Elements of the built environment include street patterns (gridded or not?), buildings (height, architectural style, materials), parking lots (where? garages?), sidewalks (width, material?), landscaping (trees?), bridges (type?), utilities (underground wires or telephone poles?), and more.

I want to share an example that I used in my recent Built Environment lecture. It’s simple, but a good place to start. Ready to play along? And, go!

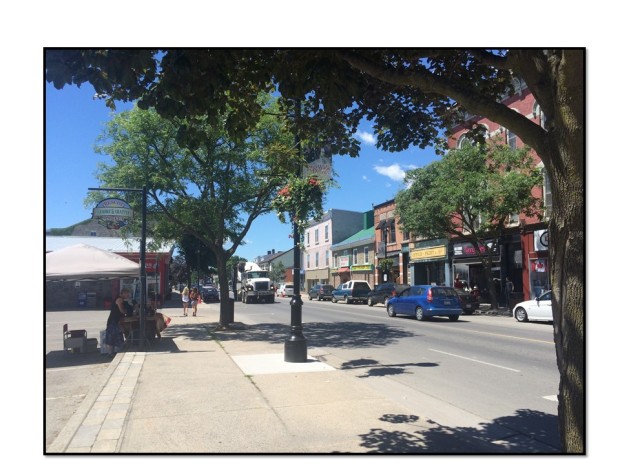

Recently, I traveled through Prescott, Ontario, a town on Canada Route 2 along the St. Lawrence River. I stopped in what appeared to be the center of town. As a preservationist, I always enjoy getting out of the car and wandering for a few blocks to snap photos and observe the area, stare at buildings – that sort of thing.

Here is the view standing on the corner of Centre Street and Route 2. Note the historic building block on the right. On the left, however, is a large parking lot. Parking lots always raise an eyebrow for me – why is there a large parking lot in the center of town? Historically, towns were not built with parking lots in the middle. Let’s have a look around.

Parking lot (left) & historic building block (right) in the center of Prescott.

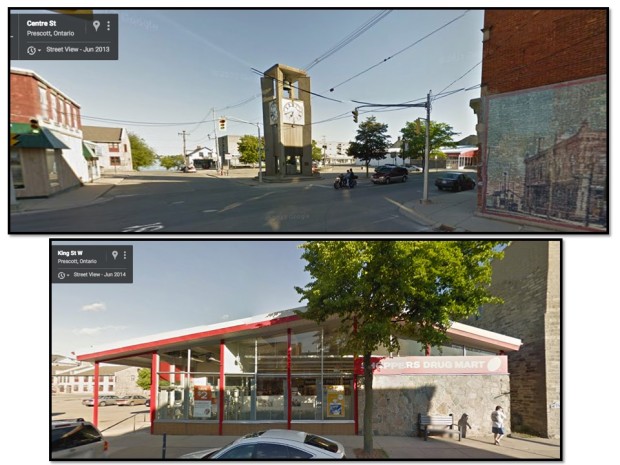

Top left: the same historic building block mentioned above. Right: tower and parking lot at the SW corner of Route 2 and Centre Street. Bottom left: The same parking lot as seen from the other end of it (note clock tower behind the tree).

You can see the photos above. Now let’s step across the street. These Google street views (below) show that SW corner (in the first photo I stood next to the clock tower).

Once I did a 360 observation of the block I had a few guesses. In the United States, if there is a hole (read: parking lot) in a town or city, I automatically think 1960s Urban Renewal era. However, this was Canada, so I wasn’t sure on Urban Renewal.

But, the drug store adjacent to the parking lot had a mid 20th century vibe (see image below). The general automobile culture (1950s/60s) often falls in line with demolition and parking lots for auto-centric businesses.

Google Street views of the corner and drug store.

My guess? A historic building was demolished for the drug store and parking lot, and the clock tower built on the edge of the parking lot to “honor” the historic building. Classic, right? Always the preservation nerd, I did some Googling to see if I could find information about Prescott development. It took a while, but eventually I did find my answer!

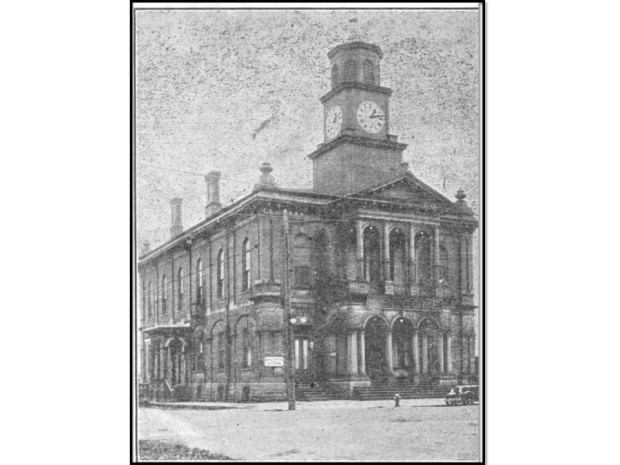

Yes, there was a historic building there. This one:

Prescott, Ontario 1876 Town Hall. The clock tower was a later addition.

According to this source, the town hall was demolished in the early 1960s due to neglect and lack of available funds in the town for repair. While I couldn’t find when the drug store was built, I have a pretty good guess that it followed shortly after demolition of the town hall.

While this was not the most uplifting example of reading the landscape, it is important to understand how our cities and towns are shaped by individual projects and decisions. And the lesson? When you see a large hole in the center, spin around and look around. It’s probably not supposed to be there.